Attacked by Fear, Protected by Wisdom

|

Psychologists call it a panic attack, but no word can do justice to the feeling you have when it happens. It is almost as if a force is attacking you, cutting off your breathing, imprisoning you inside of your own fear, leaving you with no more positive connections to the outside world. It's like being trapped in a nightmare, even you if you are awake and possibly even at one of your favourite places: at home, a shopping mall or cinema.

Once the attack has started, there's nothing you can do to stop it. If someone tries to calm you, tells you to take it easy or even "not to be silly," it usually just makes it worse. If you try to tell yourself to calm, to take it easy or "not to be silly," that will only make it worse, as well. |

As a therapist today, panic attacks are the condition I find most rewarding to work with, simply because in my younger days I suffered from them myself. In my early twenties, seemingly out of the blue, I just started to panic. Sometimes when I was at home, I was afraid to go out, when I was out, I felt afraid to go home; sometimes I was afraid to stay, sometimes I was afraid to leave. I think it is fair to say that these attacks came with a force that had the potential to ruin my life by paralysing everything I was doing.

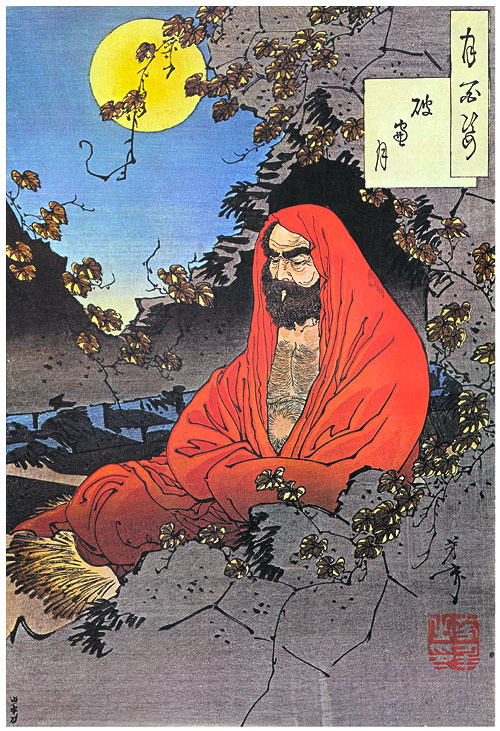

I was lucky, however, because at the time I was working as an intern at the International Campaign for Tibet, in Washington DC. As an organisation set up to help the people of the Dalai Lama, there were a lot of Buddhists. One of them was James: a lovable, quirky character. He always spent half a year working at the stock exchange, making a lot of money and inviting herds of his friends to generous rounds of drinks and food when we went out. But in the second half of every year, he went to the far East in order to study Tibetan Buddhism and meditation.

One evening I sat with a glass of red wine at some bar with James. I told him about what was happening to me, and he asked: "Did you try meditation?". At that time I did not, and couldn't even grasp the relevance. "No, I didn't," I said, "how do you do that?"

I was lucky, however, because at the time I was working as an intern at the International Campaign for Tibet, in Washington DC. As an organisation set up to help the people of the Dalai Lama, there were a lot of Buddhists. One of them was James: a lovable, quirky character. He always spent half a year working at the stock exchange, making a lot of money and inviting herds of his friends to generous rounds of drinks and food when we went out. But in the second half of every year, he went to the far East in order to study Tibetan Buddhism and meditation.

One evening I sat with a glass of red wine at some bar with James. I told him about what was happening to me, and he asked: "Did you try meditation?". At that time I did not, and couldn't even grasp the relevance. "No, I didn't," I said, "how do you do that?"

|

"Well, when I meditate," he replied, "I sit and imagine I'm on top of the mountain. From there I watch the horizon, and see clouds coming and going. I remind myself that clouds are always forming and always changing. Once they come, they will also go. It doesn't matter whether it's a small, fluffy cloud or a big, stormy cloud, it is in the nature of clouds to come, but also to go. Similarly, I ponder about my own thoughts. I realise that thoughts are like clouds: they come, but they also go. It doesn't matter whether I have a happy thought or a sad thought, a scary thought or peaceful thought, a boring thought or an exciting thought, a practical thought or a sexy thought ... whatever kind of thought, it is in its nature of a thought to come and to go."

I tried the meditation James suggested. At that time of my life, meditation was such a weird concept that I locked myself into the bathroom to do it: I didn't want my boyfriend to know what I was doing. There I sat, and tried to do what James said, and it went quite well. And within a couple of minutes, something absolutely amazing happened. I realised I wasn't my thoughts. |

I realised there was an observer behind my thoughts, and the two were not the same! Therefore, I always have the choice to identify with my thoughts or simply let them come and go like clouds. That realisation gave me the freedom and the space to learn. I understood on a deep level that panic attacks themselves consist of thoughts and feelings which come, like a big stormy cloud, but will also go. At any given time, it is my choice to stand back and wait until that cloud passes.

In therapy, we call this mechanism "dissociation." When you learn to temporarily dissociate from a fearful experience, you can begin to do different exercises which ultimately allow you to overcome panic attacks. Once you put yourself into the observer state, you can begin to apply breathing and cognitive techniques. Breathing exercises will calm you before a potential attack takes you on the roller-coaster ride of fear; cognitive techniques will help you to change those thoughts which cause your panic in the first place.

In therapy, we call this mechanism "dissociation." When you learn to temporarily dissociate from a fearful experience, you can begin to do different exercises which ultimately allow you to overcome panic attacks. Once you put yourself into the observer state, you can begin to apply breathing and cognitive techniques. Breathing exercises will calm you before a potential attack takes you on the roller-coaster ride of fear; cognitive techniques will help you to change those thoughts which cause your panic in the first place.

|

Panic attacks, over time, can become something which is in your power to control. Instead of being a victim of fear, you become a student, who becomes stronger and understands deeper and better the ultimate nature of the human mind.

When I went to professional psychologists to get some help with panic attacks, they told me that I have to learn to live with this condition, and take pills for the rest of my life, but luckily this did not prove to be the case. Today, I have lost contact with James. But if after all these years I could find out his whereabouts and see him again, I would definitely tell him: "James, you saved my life." |